An Enemy of the People

Brian--

Brian--January 31, 2005

Hey, buddy. Or should I say "Hi, Brian!" Or High Brian, perhaps. What was college like for you? Did I ever ask you that question? Was it a transforming experience -- socially and intellectually -- or was it a wasteland? Not that the two conditions, desolation and transformation, are mutually exclusive. They say that if you are going to inhabit a wasteland, you might as well be thoroughly wasted, which is itself a transformation -- transcendental or otherwise. One can be both wasted and transformed. Were you prone to transformed states in college? Put another way, did you -- shall I say, inhale? Or was your preferred intoxicant contained in a bottle?

Today I am perched somewhat precariously on a high tower. It is my refuge, my retreat. From my height -- on a cold winter's day -- I inhale the chilled but bracing air that surrounds me. From my bird's eye view above the city, I observe the hubbub below, which enlivens my day. My tower provides sanctuary and protection. I have removed myself from ordinary life. It is a precious and solitary moment. I am by myself and beside myself in my exhilaration. I stand like a puppeteer above his puppets, and in my imagination I manipulate the people I see below me, like a puppet master who animates the passive instruments under his control. I stand alone and disturb the people below me, or so I fancy.

Words, words, words . . . on some days, I have the gift . . . I can make love out of words as a potter makes cups out of clay, love that overthrows empires, love that binds two hearts together come hellfire and brimstone . . . I can cause a riot in a nunnery -- a disturbance not to be dismissed . . . but on other days . . . I feel that I have lost my gift. It's as if my quill had broken. As if the organ of the imagination has dried up. As if the proud tower of my narrative talents has collapsed. Nothing comes. And my spirits suffer.

I live to observe and to express. My capacity for vigilant scrutiny and my talent for words, for felicitous locution, enlarge my inner repository of sensual experience and permit me to make that repository accessible to my audience.

Whether my published communications unite me with others or disturb the equilibrium of their world, my own inner states are transformed thereby.

Today I am in a reflective mood. I've been thinking about desolation and transformation. I have been thinking about my current condition: my lone battle with the people, the critics, in my environment and beyond. I think about my loneliness, which rises to the level of despair at times, but, fortunately does not defeat me. I revel in my lonely struggle. I revel in my ability to disturb my immediate environment and the world beyond my imagination. I view my isolation and my defiance as virtues, the tests and marks of a higher morality. My emotional inertness pains me, but my capacity to endure my suffering and my ability to transform my distress by means of expression, by means of words, emboldens my spirit.

Something in my past must have disposed me to suffering, but at the same time prepared me to endure that very torment.

Like the proverbial professor in an academic ivory tower I have probed my problem in isolation for the past several days, ruminating about its meaning. And with the professorial pretensions that are ever my wont, I now share with you -- proud didactic adventurer that I am -- a distillation of my current thoughts.

A measure of a person's creativity, so the psychoanalysts say, is the ability to transcend the slings and arrows of outrageous critics. To be able to form a work of art out of the rubble left by such an attack is, of course, not the only way in which creative abilities can show themselves, but it is one way. I chose my view of creativity, the capacity to turn a humiliating rebuff into a triumph, for two reasons. First, it has been proposed as a developmental ideal in that it signals one of the transformations of archaic narcissism. Second, it is of particular relevance in providing a glimpse into my creative process. Specifically, I refer to my response to the criticisms and rejections of my former employer, the law firm of Akin, Gump, Strauss, Hauer & Feld, by writing my autobiography, which I titled Significant Moments. In focusing on this view of creativity, I necessarily ignore other factors that contribute to artistic creativity.

I transcended my reaction to the devastating job termination and its aftermath by creatively transforming that experience in Significant Moments. At Akin Gump I confronted central themes that had been haunting me since childhood, ghosts from the past in their purest, boldest form: my search for an idealizable father-figure (in the person of Robert Strauss), social rejection, the jealousy of coworkers (symbolic siblings), allegations that I posed a physical danger to others, the lack of empathy of peers and superiors, the appearance of anti-Semitism, and the vague impression of a corrupt organization. Having suffered for three-and-one-half years in a difficult job situation, I was in a particularly vulnerable position when attacked by the employer and ignored by potential supporters. In Significant Moments, I depicted my outrage at my former employer and coworkers, redressing the narcissistic injury I had sustained. I triumphed over my detractors through a complex self-restorative solution. I argued for an extreme, defiant, uncompromising stance through which the artist can defy social pressure and withstand ridicule and isolation; in my creative transformation I displaced my personal conflicts -- both intrapsychic and interpersonal -- onto societal conditions.

True to the best in the Jewish tradition, the conscious acceptable "enemy" for me -- as it had been for the American playwright, Clifford Odets -- would become an impersonal set of unjust and corrupt societal conditions, and the means of battle would be waged largely in words within the controllable arena of social conscience within a work of art.

My thesis is that one function of the creative process is to transform one's depleted self-state in response to a narcissistic injury. I propose that my own self-state transformation was based on motivations encapsulated in a model scene, which I inferred from a selection of recollections. A discussion of self-states and model scenes follows. The model scene links organizing themes inferred from my life and my book with the self-state I attempted to recapture after the narcissistic injury incurred by the job termination.

SELF-STATES AND THEIR TRANSFORMATION

My use of the term self-state draws on contributions from several sources: Stern's and Sander's discussions of state transformation and the self-regulating other and Kohut's discussion of self-states as noted in self-state dreams.

When used by infant researchers, state refers specifically to variations in sleep and wakefulness that occur as the infant passes between crying and alert or quiet activity, drowsiness and sleep, wet discomfort and dry discomfort, hunger and satiation. Different states affect how things are perceived, how those perceptions are integrated, and how such information is processed.

State transformations in early life accrue to both the child's self-regulation and to the expectation that mutual regulation with the caretakers will facilitate or interfere in regulating one's affects and states. Thus, early state transformations are associated with mastery or control over one's own experience, and expectations that affect regulation can (or cannot) be shared with the self-regulating other.

With the advent of symbolic capacities and increasing elaboration upon one's subjective experience, self-states in the child and adult include the domain of the self in a psychological sense. Post infancy self-state transformations may increase a sense of control, mastery, or agency, but in the case of traumatic self-state transformations, such states as devastation, outrage, or fragmentation may become dominant.

The subjective discomfort of painful self-states provides an impetus for finding means by which such states can be transformed. A creative endeavor, one means of transforming one's self-state, enhances the range of the self-regulation. Furthermore, in the context of mutual regulations, expectations of a responsive environment shift the state of the self along the dimension of fragmentation-intactness toward greater cohesion and along the dimension of depletion-vitality toward an increased sense of efficacy.

Kohut described self-state dreams in which the imagery is undisguised or only minimally disguised, depicting the dreamer's sense of self. Kohut likened these dreams to Freud's discussion of dreams in traumatic neuroses, in which a traumatic event is realistically depicted. For example, a self-state may be depicted in a dream as a barren countryside, reflecting a sense of devastation and such self experiences as depression, despair, or hopelessness.

My use of self-state is broader than Stern's since I extend my perspective into adult life, and my use of the term is not confined to the dream imagery described by Kohut. Dream imagery provides a glimpse into a person's feelings of devastation and outrage, but the imagery of narratives can also convey self-states.

MODEL SCENES

To construct the model scene that depicts the self-state that I attempted to recapture after I was subjected to devastating criticism in the form of job harassment and job termination, I combined facets of my life history.

For the first several years of my development, I experienced a childhood characterized by an overprotective but unempathic mother and a distant, but at times harsh, father. My father was a highly-intelligent man who settled for far less in life than he was capable. He had quit an academic high school restricted to college-bound students in the tenth grade, and worked at a factory job. Though he was raised in a strictly Orthodox Jewish family, he was the only one of seven children to marry outside the Jewish faith, in 1946. My mother was a Polish-Catholic whose father, an immigrant coal miner, died in the great swine flu epidemic following World War I. My father suffered both overt and covert anti-Semitism from my mother's family during the marriage -- itself a form of criticism. My father coped with the attacks directed at him by relying on a deeply-rooted sense of his cultural and religious superiority.

My mother doted on me, but paradoxically, had a tendency to negligent, even reckless, caretaking. At age three I developed scarlet fever, an unusual bacterial disease. I was late in being weaned from the bottle. Though I ate solid food by age three, of course, my mother indulged my desire to drink milk that had gone sour in the bottle. The pediatrician, Dr. Bloom, who diagnosed the illness attributed it to the sour milk. "And why is he still drinking from a bottle? He's too old to be drinking milk from a bottle," the doctor said. (Dr. Bloom! "Just who does Dr. Bloom think he is?"). My father was very angry, and chastised my mother bitterly for "spoiling" me, in the doctor's presence. I felt humiliated and helpless in the face of the charges leveled at me. My secret oral perversion had been discovered! The secret was out! The doctor advised my parents that scarlet fever was considered a serious public health concern, and that he was bound by law to report my illness to the city health department. Several days later, the health department posted a quarantine notice on the front door of our home (1957). My private act led to unforeseeable consequences in the form of intervention by a government authority. In effect, at age three the government had determined that I was already "potentially dangerous."

The scarlet fever incident contributed to the centrality of solitary self-experience for me. From an experience of pleasure (in drinking sour milk from the bottle), I was suddenly transformed to a state of loss and an inexplicable sense of guilt. I felt like a felon and, if you will excuse the hyperbole, "would hide when the constable approached the house." The illness ushered in transformation from a positive, pleasurable, self-absorbed state to a secret state marked by guilt and a personal blame for wrongdoing. I did not find solace for my loss. On my own, I bore both my guilt and the surprising, disturbing impact I could have on others in my immediate world and beyond: indeed, reaching out to a world beyond my imagination, in the form of governmental authorities. The illness also signaled another transformation in the direction of having to regulate painful states on my own without the support of others. Both parents were concerned with public embarrassment, rather than with the state of their child. I propose that the model scene I have constructed organized my experience as a solitary, impactful onlooker: someone whose private actions could even trigger the intervention of government authorities. It is an experience that few three-year-olds have. An emotionally porous three-year-old who is "hypersensitive to the goings-on in his environment," cf. Freedman v. D.C. Dept. of Human Rights, DCCA 96-CV-961 (Sept. 1998), will be affected by that experience.

This letter, and particularly the above anecdote, is a metaphorical bridge of speculation that connects mystery to mystery, the known with the unknown. That bridge is like a single plank that requires the support of others to form a firm foundation. I offer the following thought. My age upon contracting scarlet fever, which resulted from my mother's indulgence of my dependency needs -- age three or three-and-a-half -- is the same age my mother was when her father died of a communicable disease, influenza: in an influenza epidemic that, because of its magnitude, had evoked a vigorous public health response by government authorities nationwide. Is it possible that my "good" mother was instrumental in setting me up for serious illness? Was my mother's seeming indulgence really an expression of a strong unconscious ambivalence toward me that was a derivative of her emotional reaction to her own father's death?

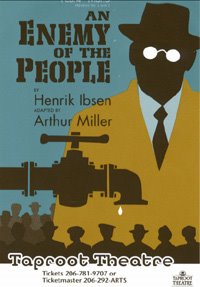

Incidentally, the anecdote above parallels themes in several plays by Henrick Ibsen. In Ghosts a mother provides poison to her son to enable the son's suicide in expiation of his father's sins; An Enemy of the People pits a truth-fanatic (who discovers that the waters of a spa town are polluted) against the town's mayor and its citizens; and in The Master Builder a mother, out of a perverse sense of duty, kills her twins -- she contracted a fever because she could not stand the cold, but, despite the fever, she insisted on breast-feeding the twins, who died from her poisoned milk.

Note that I was the only male child in the family. Oddly, when I was a young boy, my older sister created the fiction that my middle name was "Stanley," my mother's father's name. I actually came to believe at one point in childhood that my name was "Gary Stanley Freedman."

Be that as it may.

My mother had a passionate interest in motion pictures and, in childhood, was fond of playing with dolls. I picked up on these interests in a way. In early adolescence I developed a fanatic attraction to the Wagner operas, and I had an interest in the craft of play writing. In high school and college I took elective courses in drama and theater. At age thirteen I staged (after a fashion), in the basement of our family home, a highly-abbreviated version (to say the least) of Wagner's four-opera Ring Cycle for the entertainment of my parents -- though, in reality, my parents were uninterested, if not hostile to my effort.

My father was subject to bouts of depression and sometimes became bitter and brutal toward my family, but he took no steps to change his situation, other than threatening, from time to time, to leave my mother. He was frequently morose and withdrawn. I reacted to my father throughout childhood with a range of irreconcilable emotions: idealization, sympathy, anger, and fear. Sound familiar, buddy?

Taken as a unity, to be spelled out below, these accounts suggest that, for me, self-states and affects had to be regulated alone, by myself. In later life, I transformed my despondent state after my critical rebuff at Akin Gump by drawing on the themes encapsulated in the model scenes.

In psychoanalytic treatment, analyst and patient construct model scenes to convey, in graphic and metaphoric forms, significant events and repeated occurrences in the analysand's life. The information used to form model scenes can be drawn from a variety of sources, including a patient's narrative and recollections. Model scenes highlight and encapsulate experiences at any age, not only early childhood, and are representative of salient conscious and unconscious motivational themes. The concept of model scenes is broader than and includes screen memories, which Freud equated with the manifest dream content dream, in that they point toward something important that they disguise. The memory itself and its "indifferent" content are to be discarded as the analyst recovers and reconstructs the significant, concealed childhood event or fixation. Whereas screen memories focus on reconstructing what has happened, model scenes pay equal attention to what is happening, whether it is in the analytic transference or in the person's life. For me, the model scene is based on recollections that capture my solitary self-regulation, self-restoration, and my triumph over my detractors.

MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY: SIGNIFICANT MOMENTS

The book is unusual in structure. It is drawn exclusively from published literature -- it is a collection of quotations, really -- with the quotes woven together to form a cohesive narrative, comparable in a sense to the structure of T.S. Eliot's "The Wasteland." A single, cohesive narrator or hero does not appear in the book. Rather, the author manipulates the quotations; he hovers overhead, as it were, like a puppet master, pulling all the strings. I am represented, through my identification with various literary and historical figures, by identity elements or identity fragments, which are the quotations. The themes of the book are numerous and diverse. The themes include anti-Semitism, the craft of writing, opera production, communicable disease, genetics, inheritance, the discovery of a secret that brings ruin on the discoverer, scientific discovery, truth seekers, critical response by peers, defiance of peers and authorities, banishment and social isolation, the absence of an empathic or supportive environment, the self-regulation of affects, the death of fathers, the intervention of government authorities into the private domain of citizens, the seductive or destructive mother, alleged corruption and cover-up, among other topics.

CRITICISM AND RESPONSE

The negative response I received upon my job termination and its aftermath was diffuse. It came from the employer, psychiatrists (doctors), and government authorities. If I were asked why I began to write my autobiography in April 1993, four months after I had received the employer's responsive pleadings in a legal action I had initiated against the employer, I would have said: "I had to write my autobiography."

In Significant Moments, "the hero" (who appears in various guises, or is represented by various identity elements) makes a discovery that results in his being pitted against "the powers that be." The detractors of "the hero" are mocked and exposed as mean-spirited and unprincipled. I thereby expressed my distrust of the capacity of the "majority" to discriminate the "true" from the "false" and to exercise sound judgment. I showed "the powers that be" to be swayed by self-interest and incapable of distinguishing scientifically backed findings from self-serving rationalizations.

There is no decent, supportive public in Significant Moments. "The hero" naively values the support of "the powers that be" at the opening of the book. He believes that they will be responsive to truth and evidence. Before the book's end, "the hero" could rightly say that the most dangerous enemy of truth and freedom amongst us is the solid majority. "The majority is never right! . . . The minority is always right!" The minority to which "the hero" refers is himself. By the end of the book, he can trust nothing but his own values, perceptions, and beliefs.

Wounded by the shortsighted managers at Akin Gump, I asserted that the creative artist stands alone, a minority of one, to maintain his integrity and the purity of his vision. In Significant Moments I spoke with one uncompromising, solitary voice clearly depicted in "the hero," who loses all support and ends alone. "The strongest man in the world is the man who stands most alone." Increasing isolation drives "the hero" to proclaim, "I want to expose the evils that sooner or later must come to light."

To explore and to react aversively are dominant motivations for "the hero." He is uncompromising to the end, a man who does not mean to settle for rapprochement with the majority. He was ready to bring ruin upon himself and others rather than "flourish because of a lie."

In my response to the critics, I presented my hero as totally decent and honest, but naive with respect to political wheeling and dealing. His decency and goodness are contrasted with the narrow-mindedness of the majority. They are devoid of a sense of morality of their own and led by authorities who are rigid, unimaginative, self-serving, and bureaucratic -- banal at best and corrupt ("poisoned") at worst.

CREATIVE TRANSFORMATION: FROM JOB TERMINATION TO SIGNIFICANT MOMENTS

I had to write Significant Moments. The themes of that book, father-son tensions (real or symbolic), living a lie, the effects of learning "the truth," inheritance (in my case, the transmission of parental strengths and weaknesses), all manifestly rooted in my early life, are taken up in my book. In so doing, I addressed my compelling, burning, residual issue from my past and depicted it as a metaphor for my society as well. Significant Moments thus combines painful memories with a devastating social critique. Personally, I expressed my disillusionment at my father's legacy of academic, occupational, and marital failure, as well as my quest for an idealizable father of whom I could be proud.

Apparently I felt compelled to bare myself in a barely disguised form. I gathered together my past grievances and projected them on to "The Freud Archives Board." In them I embodied the lies, hypocrisy, deception, and duplicity that I hated in society. So long as they typified "the powers that be" and its "opinions," there could be no compromise. My uncompromising depiction of the "sins of the father," the "ghosts" that demand placing duty and public appearances above self-expression and individual freedom, expresses my long-held convictions in the purest, boldest form.

At the center of Significant Moments lies my determination to explore two sides of deception. Some self-deception is held necessary to maintain hope and to survive, yet there is also a pernicious self-deception that erodes ethics and undermines morality. Both Nietzsche and Jeffrey Masson were compelled to counter, respectively, Wagner's and The Freud Archives' deceptions of themselves and others. "The Heroes'" (Nietzsche's and Masson's) duty-bound rejection was felt by "the powers that be" (Wagner and Dr. Eissler) as both a rejection of their ideals and a personal betrayal.

I was shocked by my sudden job termination in late October 1991; but later (in April 1993), within four months of receiving the employer's responsive pleadings in the agency complaint I filed, I began work on Significant Moments. With my self-confidence shattered, if there was a moment when the capacity to transform shattered narcissism into artistic creativity was called for, this was it. The book became my response to the devastating experience of my termination and its aftermath. Note that it was only upon my receipt in late December 1992 of the employer's pleadings that I learned that the employer had allegedly determined that I was potentially violent -- that is, a physical danger to others: an allegation that must have resonated with my memory that at age three I had been determined by a municipal authority to pose a public health risk.

In Significant Moments moral integrity on one side is pitted against deception, greed, and narrow self-interests on the other. The battle lines are drawn clearly. Perhaps in outrage, all gloves are off. I myself step upon the stage and drag my enemy, conventional wisdom, front and center with me.

The hero pays the price for his naive belief in truth; he is socially totally isolated, but he remains undaunted. Throughout the book, he remains loyal to the idea that truth will win the day. He utters the line (through playwright Arthur Miller) that embodies "the hero's" defiance of the "majority" and defines the state in which he feels himself to be: independent, invulnerable, and exquisitely self-contained. "The strongest man in the world is the man who stands most alone!"

To me, the artist's strength lays in an undaunted capacity to maintain a vision in the face of opposition and to "cleanse and decontaminate the whole community." I must disturb, be perpetually misunderstood, and walk alone. Yet I would call Significant Moments an expression of the "comedy of life" in that it expresses my recognition that the creative artist cannot totally stand alone. Ultimately, he needs an audience to respond to him.

CREATIVITY IN SELF-STATE TRANSFORMATION

The artist accepts isolation as a consequence of his superior, unique vision of the world. He depicts his ideal, to follow the dictates of his artistic integrity, irrespective of the consequences. Compromise means accommodating to societal pressures, hypocrisy, and deception.

In Significant Moments the tyranny of conventional wisdom, the legacy of father to son, and the strength inherent in one's solitary loyalty to the "ideal" of truth appear on an unadorned stage.

It is always risky, when discussing an artist, to draw inferences about his life from his creative output. Nonetheless, parallels do exist between the artist's life and his creative work.

Traumatic, painful, or humiliating life experiences sometimes provide the context for an artist's work. To some extent, the creative product is the transformation by the artist of the effects of his painful past and narcissistically injurious experiences. Here, transformation refers to self-regulated alterations, the capacity to alter one's self-state, when, for example, it is characterized by guilt or shame, stirred by feelings of defeat and, when exposed to contempt, derision, or ridicule. To turn painful self-states into a sense of triumph requires transforming narcissistic injuries, often though not invariably, via narcissistic rage, into a sense of having righted a wrong, avenged a slur, or seized self-"intactness" from the jaws of injury.

Significant Moments is a self-revelation. As the book proceeds headlong toward its tragic denouement, the passages that describe the weather and the lighting are psychologically revealing. Thus, the portion of the writing that describes the high point of the Wagner-Nietzsche relationship refers to the brilliance of the sun. While the last meeting of Wagner and Nietzsche takes place on a cold, drizzly evening -- the night of a dinner party. Artists, including myself, often depict self-states of the characters through, for example, reference to weather. Changes in the weather foreshadow, just as a dream of a barren countryside may reveal and foreshadow, the state of the self.

The book also contains numerous biblical allusions and quotations. In adult years I have stood alone against my critics, who have usually been stronger and more numerous than my defenders. The source of my strength -- my ability to stand alone, undaunted -- I believe, is ultimately a positive inheritance from my father: namely, my father's ego-strengthening identification with the historical struggle of the Jewish people for survival. My ambivalence toward my father now becomes more understandable. My "inheritance" did not only include my father's failings, but contained a substantial quantum of support from him as well. My solitary faith in myself and my eventual triumph, coupled with my memory of my father's loyalty to the best in the Jewish tradition, may have provided the strength that has enabled me to stand alone and continue my struggle without the aid or presence of another.

After my disappointing job termination in 1991, my self-state could be characterized as enraged by new disappointments, as well as the revival of the old hurts and disillusionments. I sought refuge through the transformation of my painful state to one that may also have been an enduring legacy of my childhood, a state devoid of impingements from others and free of the disappointment I felt in my father. I sought a sense of supremacy, alone and at peace. Akin to a puppeteer, I longed to be above the critics and the mundane world, without concern for social status, economics, or prestige.

In any event, that's the bird's eye view.

Check you out next week, buddy. You might want to look up Bruce S. Linenberg, who was in my high school graduating class. He was supersmart and supercool. He's now a psychologist.

P.S. This letter is, for the most part, a paraphrase of a technical paper: "Ibsen: Criticism, Creativity, and Self-State Transformations," by Frank M. Lachmann and Annette Lachmann, published in The Annual of Psychoanalysis, vol. 24, 1996.

Frank M. Lachmann, Ph.D., is a member of the Founding Faculty of the Institute for the Psychoanalytic Study of Subjectivity; Clinical Assistant Professor, New York University Postdoctoral Program in Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis, and Training and Supervising Analyst, Postgraduate Center for Mental Health. He is author or co-author of more than 80 publications. His most recent works include Transforming Aggression: Psychotherapy with the Difficult-to-Treat Patient (Aronson, 2001); with Beatrice Beebe he is co-author of Infant Research and Adult Treatment: Co-Constructing Interactions (Analytic Press, 2002) and with Joseph Lichtenberg and James Fosshage he is co-author of three books, including A Spirit of Inquiry: Communication in Psychoanalysis (Analytic Press, 2002).

APPENDIX: Brief excerpt from Significant Moments, an autobiographical study.

Those with an intimate acquaintance of Hebrew texts will recognize immediately that this one is written entirely in melitzah, a mosaic of fragments and phrases from the Hebrew Bible as well as from rabbinic literature or the liturgy, fitted together to form a new statement of what the author intends to express at the moment. Melitzah, in effect, recalls Walter Benjamin's desire to someday write a work composed entirely of quotations. At any rate, it was a literary device employed widely in medieval Hebrew poetry and prose, then through . . .

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Freud's Moses.

. . .the movement known as Haskalah, Hebrew for “enlightenment,”. . .

Herbert Kupferberg, The Mendelssohns: Three Generations of Genius.

. . . and even among nineteenth-century writers both modern and traditional.

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Freud's Moses.

What is so special about this particular . . .

Adam Baer, The Music Language.

. . . literary device?

Ken Ham, Where are you, metaphor?

In melitzah the sentences compounded out of quotations mean what they say; but below and beyond the surface they reverberate with associations to the original texts, and this is what makes them psychologically so interesting and valuable. In the transposition of a quotation from the original (in this case canonical) text to a new one, the meaning of the original context may be retained, altered, or subverted. In any case the original context trails along as an invisible interlinear presence, and the readers, like the writer, must be aware of these associations if they are to savor the new text to the full. A partial analogy may be found in Eliot's use of quotations in The Waste Land.

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Freud's Moses.

If he is successful in . . .

Donald P. Spence, Narrative Truth and Historical Truth: Meaning and Interpretation in Psychoanalysis.

. . . his use of melitzah, . . .

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Freud’s Moses.

. . . the Author . . .

Bill Moyers, Genesis: A Living Conversation.

. . . will arouse in the reader a particular set of images and associations which will add a certain texture and tone to what is being described—the chordal accompaniment, so to speak, to the melodic line.

Donald P. Spence, Narrative Truth and Historical Truth: Meaning and Interpretation in Psychoanalysis.

_____________________________________________________________

I have resolved on an enterprise which has no precedent, and which, once complete, will have no imitator. My purpose is to display to my kind a portrait in every way true to nature, and the man I shall portray will be myself. Simply myself.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Confessions.

If I have written much of it in the third person, well, that is because such an obsessive account of . . .

Richard Selzer, Raising the Dead.

. . . my intrusion into this valley of suffering . . .

Arthur Rubinstein, My Young Years.

. . . forces one, like Dorian Gray, to confront his own "devilish, furtive, ingrown" self-portrait. The pronoun he gives a blessed bit of distance between myself and a too fresh ordeal in which the use of I would be rather like picking off a scab only to find that the wound had not completely healed.

Richard Selzer, Raising the Dead.

In the career of the most unliterary of writers, in the sense that literary ambition had never entered the world of his imagination, the coming into existence of the first book is quite an inexplicable event. In my own case I cannot trace it back to any mental or psychological cause which one could point out and hold to. The greatest of my gifts being a consummate capacity for doing nothing, I cannot even point to boredom as a rational stimulus for taking up a pen.

Joseph Conrad, A Personal Record.

What kind of person am I? What is so special about me?

Richard Wagner, Letter to King Ludwig II of Bavaria.

I am an assimilated Jew, content to be assimilated, relieved to be religiously unobservant. I don't know any Hebrew, or have forgotten the little I once learned.

Wayne Koestenbaum, Listening to Schwarzkopf: The Reich and the Soprano.

Speaking personally, I find that the American experience of being an assimilated grandchild of Orthodox immigrants has tended to make me an ill-informed, nonbelieving, non-observant Orthodox Jew, haunted by nostalgia for the peculiar music of the shul, for the Judaism I do not practice. And this adds still another puzzling iridescence to my Jewishness and to the tantalizing opportunities of my writer's divided self.

Daniel J. Boorstin, Cleopatra's Nose: Essays on the Unexpected.

. . . since these pages, if they survive me, may be the last testament of my brief and insignificant passage through the world, let me scrawl out the main facts.

Herman Wouk, War and Remembrance.

"I come from an unbroken line of infidel Jews. My father was a Voltairian. My mother was pious, but one day my father took me out for a walk . . .

Sigmund Freud, Conversation with Thornton Wilder.

. . . a walk in a little neighboring wood . . .

Voltaire, Candide.

. . . I can remember it perfectly, and explained to me that there was no way we could know that there is a God; that it didn't do any good to trouble one's head about such; but to live and do one's duty among one's fellow men"

Sigmund Freud, Conversation with Thornton Wilder.

I know my own heart and understand my fellow man. But I am made unlike any one I have ever met; I will even venture to say that I am like no one in the whole world. I may be no better, but at least I am different. Whether Nature did well or ill in breaking the mould in which she formed me, is a question which can only be resolved after reading my book.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Confessions.

____________________________________________________________

We writers live in the limbo between expression and communication. And we do not need theology or metaphysics to remind us that as writers we cannot avoid the effort, or the temptation, to serve two masters—ourselves, what is within us, and our reader, our conjectural clients outside.

Daniel J. Boorstin, Cleopatra's Nose: Essays on the Unexpected.

I, on my side, require of every writer, first or last, a simple and sincere account of his own life, and not merely what he has heard of other men's lives; some such account as he would send to his kindred from a distant land; for if he has lived sincerely, it must have been in a distant land to me. Perhaps these pages are more particularly addressed to poor students. As for the rest of my readers, they will accept such portions as apply to them. I trust that none will stretch the seams in putting on the coat, for it may do good service to whom it fits.

Henry David Thoreau, Walden.

By an ironic twist in the history of western literature, in this very age of unprecedented temptations to literary populism, an age of the sovereign and increasingly demanding public, there developed a fertile new sense of Personal Conscience. The private consciousness took on a new life and became a wondrous new literary resource. In modern transformation, conscience, an ancient laboratory of theological hairsplitting and a modern arena of ephemeral public taste, became inward, experimental, and biographical.

Daniel J. Boorstin, Cleopatra’s Nose: Essays on the Unexpected.

But more. But infinitely more.—

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Case of Wagner.

As prophet and pundit . . .

Daniel J. Boorstin, The Creators: A History of Heroes of the Imagination.

. . . as devilish, dangerous, a rebel, and yet also a martyr and sacrifice . . .

Frederick Karl, Franz Kafka: Representative Man.

. . . the writer has become . . .

Ramakant Rath, Has Literature a Future?

. . . the bad conscience of our whole era, . . .

Cosima Wagner’s Diaries (Monday, December 13, 1869).

. . . and in so doing indeed . . .

Henry James, Confidence.

. . . he has come perilously close to defining the modern . . .

Frederick Karl, Franz Kafka: Representative Man.

. . . antihero who rejects received tenets of behaviour and stays true to his individuality . . .

Youssef Rakha, Review of A Sun Which Leaves No Shadows.

. . . in an always alien society.

Frederick Karl, Franz Kafka: Representative Man.

To think of the writer as conscience of the world is only to recognize that the writer, . . .

Daniel J. Boorstin, Cleopatra's Nose: Essays on the Unexpected.

. . . as we shall see, . . .

Edward R. Tannenbaum, 1900: The Generation Before the Great War.

. . . is inevitably a divided self, condemned at the same time to express and to communicate, to speak for the writer and speak to others.

Daniel J. Boorstin, Cleopatra's Nose: Essays on the Unexpected.

The orator yields to the inspiration of a transient occasion, and speaks to the mob before him, to those who can hear him; but the writer, whose more equable life is his occasion, and who would be distracted by the event and the crowd which inspire the orator, speaks to the intellect and heart of mankind, to all in any age who can understand him.

Henry David Thoreau, Walden.

Western literature offers us countless different ways in which authors have dealt with this divided self. I will provide only a sample from some of my favorite writers that may suggest the perils that beset writers who pretend to be the world's arbiters.

Daniel J. Boorstin, Cleopatra's Nose: Essays on the Unexpected.

Like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, . . .

Richard M. Ashbrook and Michael W. Torello, Preserving Community in a Technological Age: Toward the Constructive Incorporation of Technology in Higher Education.

. . . Hermann Hesse . . .

K.R. Eissler, Talent and Genius.

—one of my favorites—

Christina Olson Spiesel, The One Who Loved My Work: A Meditation on Art Criticism.

. . . embodied those divisions of his age which have left their mark on our culture. . . . In a manner unique among writers, he wove his immediate experiences into his books to portray many of the dilemmas and historic crises of his time. . . . It was this finely tuned interaction between his psychological conflict and historical events that was to make him a poet of crisis. . . .

Hesse's stories—like the dreams he collected in special notebooks—are told from both conscious and unconscious experience and therefore reveal and conceal events, encounters, and feelings from himself, his friends, his public. The way Hesse lived and wrote about his life, constantly aware of his conflicting impulses as part of the tension of his art, made this revelation and concealment permeate all his writings. . . .

He made himself into an example for his readers, just as Rousseau, by no means a stranger to the art of disclosure and concealment, had presented himself in his Confessions. With its "pole" and "counterpole," Hesse's work became an ongoing act of instruction even as it took the shape of a continuous novel.

Ralph Freedman, Hermann Hesse: Pilgrim of Crisis.

____________________________________________________________

The popular literary form . . .

Daniel J. Boorstin, Cleopatra's Nose: Essays on the Unexpected.

—as opposed to the sequestered academic one—is always straining at the inbuilt inertia of a society that always wants to deny change and the pain it necessarily involves. But it is in this effort that the musculature of important work is developed.

Arthur Miller, Timebends.

Hesse's literary career was closely interwoven with his personal fortunes as well as with his philosophical interests. His works before his disillusionment in World War I reflect the German literary traditions of romanticism and regionalism.

Encyclopedia Americana.

In this tradition, we are dealing with a line of thought that frames . . .

Ghent Urban Studies Team, The Urban Condition: Space, Community, and Self in the Contemporary Metropolis.

. . . clear-cut distinctions between good and evil, prudence and folly, reality and fantasy.

Edward R. Tannenbaum, 1900: The Generation before the Great War.

At any rate, in . . .

Erik H. Erikson, Young Man Luther.

. . . accord with his original artistic nature, . . .

Paul Roazen, Erik H. Erikson: The Power and Limits of a Vision.

. . . and at a time when . . .

Michael Nightingale, Smallpox: Why All The Fuss?

. . . in his youth . . .

Erik H. Erikson, Young Man Luther.

. . . he has not yet seen any of his illusions dissipated, . . .

Hermann Hesse, Magister Ludi: The Glass Bead Game.

. . . Hesse’s . . .

Ralph Freedman, Hermann Hesse: Pilgrim of Crisis.

. . . generally lower-middle-class heroes work hard, though rarely successfully, at adjusting to . . .

Encyclopedia Americana.

. . . the technological and social change . . .

Erik H. Erikson, Young Man Luther.

. . . of urban industrial society.

Edward R. Tannenbaum, 1900: The Generation Before the Great War.

By the time . . .

Martin Gregor-Dellin, Richard Wagner: His Life, His Work, His Century.

. . . the Great War ended, however, . . .

W. Thomas White, Working Life: The Big Strike.

. . . the world had undergone a complete transformation . . .

Martin Gregor-Dellin, Richard Wagner: His Life, His Work, His Century.

. . . and the consequences for . . .

Hermann Hesse, Magister Ludi: The Glass Bead Game.

. . . Hesse . . .

K.R. Eissler, Talent and Genius.

. . . himself were far greater than he could ever have foreseen.

Hermann Hesse, Magister Ludi: The Glass Bead Game.

Somehow events in his life were coming to a head, but he felt that he was being lived by them, rather than living them.

Erik H. Erikson, Young Man Luther.

He became uncertain whether good and bad, right and wrong, had any absolute existence at all. Perhaps the voice of one’s own conscience was ultimately the only valid judge, and if that were so, then . . .

Hermann Hesse, Magister Ludi: The Glass Bead Game.

Each man had only one genuine vocation—to find the way to himself. He might end up as poet or madman, as prophet or criminal—that was not his affair, ultimately it was of no concern. His task was to discover his own destiny—not an arbitrary one—and live it out wholly and resolutely within himself. Everything else was only a would-be existence, an attempt at evasion, a flight back to the ideals of the masses, conformity and fear of one’s own inwardness.

Hermann Hesse, Demian.

What more need I say?

Mohandas K. Gandhi, Indian Home Rule.

Beginning with Demian (1919), . . .

Encyclopedia Americana.

—if we may be permitted to anticipate our story . . .

Hermann Hesse, Magister Ludi: The Glass Bead Game.

. . . his heroes no longer try to conform but . . .

Encyclopedia Americana.

. . . force themselves almost against their own wills to insist, at the price of isolation, on finding an original way of . . .

Erik H. Erikson, Young Man Luther.

. . . participating in . . .

H.G. Wells, The World Set Free.

. . . a new age of human involvement and commitment.

Encyclopedia Americana.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home